Tol Massacre |

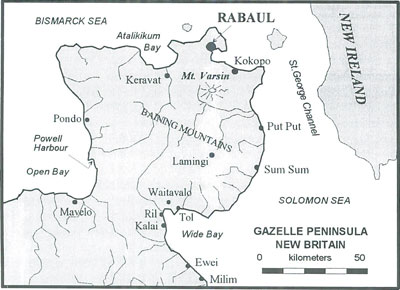

Approximately 1,050 Australian soldiers from Lark Force were taken prisoner by the Japanese in the Rabaul/East New Britain area in January/February 1942. Many of these were murdered on or about 4 February in the vicinity of Tol and Waitavalo Plantations at the eastern end of Wide Bay on the south coast of New Britain. The soldiers had escaped down the east coast from Rabaul and were rounded up by the Japanese while waiting to cross flooded rivers to move further west.

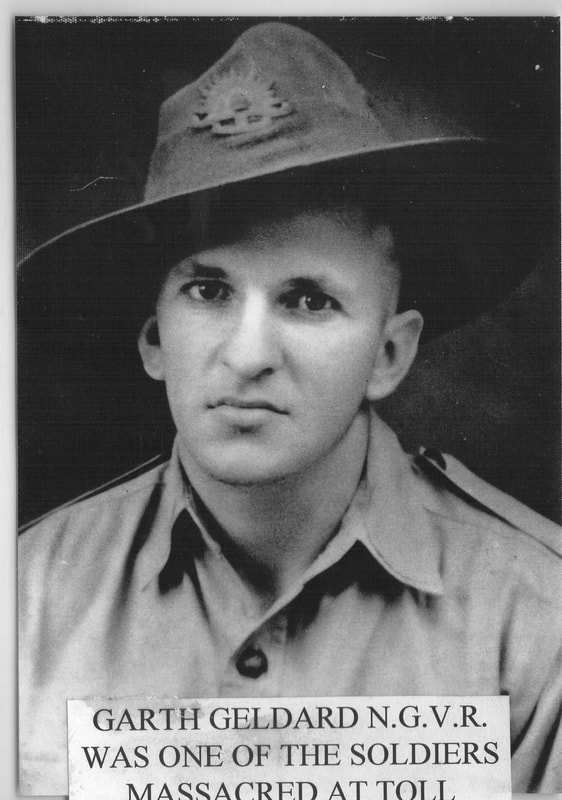

After the war, 158 bodies were discovered in the vicinity of Tol and Waitavalo Plantations. The survivors later described how they were rounded up on the 3 February and in the early morning of the 4th February, tied up in small groups, lead into the jungle and bayoneted or shot by Japanese soldiers. There were four separate mass murders on that day. The Japanese officer responsible for these war crimes was Colonel Masao Kusunose who later committed suicide. It is known that eight of the soldiers taken away to be murdered were from NGVR including a survivor A L Robinson, who escaped while being led into the forest. Days later, Robinson met up with Frank Holland and with 29 other men, escaped via the north coast of New Britain. Only six other soldiers from Lark Force escaped from the Tol massacre. The statement made by then Pte A.L. Robinson regarding the Toll Massacre, as well as his survival story, is included in the book “Keepers of the Gate” by MAJ. F.J. (Bob) Collins. – see “suggested reading |

Japnese troops in Rabaul

Japnese troops in Rabaul

A macabre end awaited the Butcher of Tol

It was late in 1946 and Colonel Masao Kusunose, 58, was about to be tried by the Allies.

The reason: at Tol Plantation on New Britain on 4 February 1942, he had authorised the bayoneting to death of 160 Australian prisoners. The prisoners were military and civilian escapees from the Japanese invasion of Rabaul. Tired, hungry and demoralised after nearly two weeks in the jungle, they had decided to surrender. A couple of men miraculously survived the slaughter, and escaped to tell the story.

The Colonel, according to his peculiar code, was a man of honour. For him there was only one possible course: suicide. He could not commit hara-kiri because his samurai sword had been confiscated by the Allies. Death by drowning or jumping in front of a train would be improper. So he decided to end his life by starvation and exposure in the sub-zero weather.

While Allied authorities hunted him, Kusunose went to the foot of Fujiyama, to a deserted army barracks where he had soldiered as a youth. He sat down facing the great mountain, which rose so steeply above him he had to bend his head back to see the splendor of the sunlit, snowcapped summit. Kusunose sat down on December 9. On December 17 or 18, Death, which had been creeping nearer for nine days, sat down beside him. As he sat dying, Kusunose covered 15 pages of his small black Japanese army notebooks with entries. He had been a soldier; he was dying as a soldier. The last entries concerned food and hunger. On the last two days, he mentioned pains in his stomach and legs. His last entry was scrawled in red crayon: “Heaven will preserve Japan and the Emperor.”

When an Allied search party reached the barracks at the foot of Fujiyama, they found an old straw sandal, a chopstick and a rusty can. (Japanese lacking Kusunose's peculiar sense of honour had long since looted everything else. The searchers also found Kusunose's body. But it no longer faced the sacred mountain. Before he died, Kusunose had found the strength to turn away. The diary explained why: “It would be disrespectful if I died in the presence of revered Fuji.”

Kusunose's left eye had been eaten away by rats.

Source: Time Magazine, 3 February 1947

It was late in 1946 and Colonel Masao Kusunose, 58, was about to be tried by the Allies.

The reason: at Tol Plantation on New Britain on 4 February 1942, he had authorised the bayoneting to death of 160 Australian prisoners. The prisoners were military and civilian escapees from the Japanese invasion of Rabaul. Tired, hungry and demoralised after nearly two weeks in the jungle, they had decided to surrender. A couple of men miraculously survived the slaughter, and escaped to tell the story.

The Colonel, according to his peculiar code, was a man of honour. For him there was only one possible course: suicide. He could not commit hara-kiri because his samurai sword had been confiscated by the Allies. Death by drowning or jumping in front of a train would be improper. So he decided to end his life by starvation and exposure in the sub-zero weather.

While Allied authorities hunted him, Kusunose went to the foot of Fujiyama, to a deserted army barracks where he had soldiered as a youth. He sat down facing the great mountain, which rose so steeply above him he had to bend his head back to see the splendor of the sunlit, snowcapped summit. Kusunose sat down on December 9. On December 17 or 18, Death, which had been creeping nearer for nine days, sat down beside him. As he sat dying, Kusunose covered 15 pages of his small black Japanese army notebooks with entries. He had been a soldier; he was dying as a soldier. The last entries concerned food and hunger. On the last two days, he mentioned pains in his stomach and legs. His last entry was scrawled in red crayon: “Heaven will preserve Japan and the Emperor.”

When an Allied search party reached the barracks at the foot of Fujiyama, they found an old straw sandal, a chopstick and a rusty can. (Japanese lacking Kusunose's peculiar sense of honour had long since looted everything else. The searchers also found Kusunose's body. But it no longer faced the sacred mountain. Before he died, Kusunose had found the strength to turn away. The diary explained why: “It would be disrespectful if I died in the presence of revered Fuji.”

Kusunose's left eye had been eaten away by rats.

Source: Time Magazine, 3 February 1947

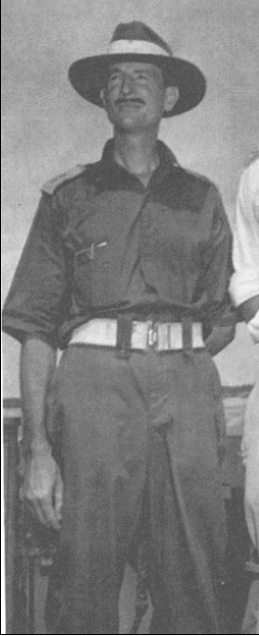

Bill Collins. Survivor

LT A.L. Robinson on Manus Island, 1944 where he was awarded the DCM for his actions in assisting the US 5th Cavalry Regt, 1st Cavalry Div. during their landing. Read his statement about his escape from the Tol massacre below.

| A.L.Robinson Statement | |

| File Size: | 17 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

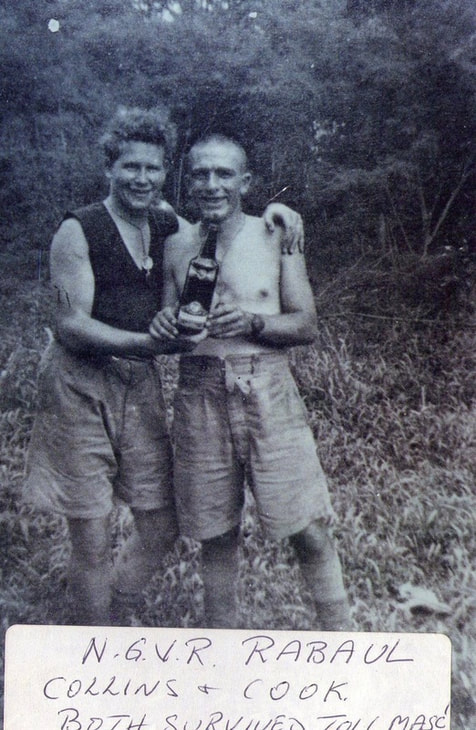

Private William Cook, 2/10th Field Ambulance, one of the few survivors of the Tol massacre in New Britain. He received 5 wounds and was left for dead. Unable to hold his breath, he received another 6 bayonet wounds.

[P01395.003]

[P01395.003]